Hi there! Welcome to Iris Writes. I’ve been thinking about starting a Substack for years now, and on Jan 1st of this year I told myself I’d finally launch it. And then the wildfires happened, and January felt like the longest month, and here we are in mid-February. But I’m grateful for the reset that Lunar New Year brings.

So without further ado, here’s my first post…

It’s Lunar New Year, and I’ve just interviewed a dozen people about their grief.

This past year, there was a succession of grandparents’ deaths in my friend group. It feels like an inevitability in the circle of life—as we hit our late 20’s, our grandparents will leave us, if they haven’t already. And in the wake of their deaths swirls a confusing cloud of grief.

Many of my friends admitted not being very close to their grandparents, and not exactly feeling the expected depth of emotion. They witnessed their parents' bottomless grief, but weren't sure how much weight to place on their own. They were a bit sheepish as they acknowledged this lack of feeling, as if grief is a standard measure that a mourner must meet.

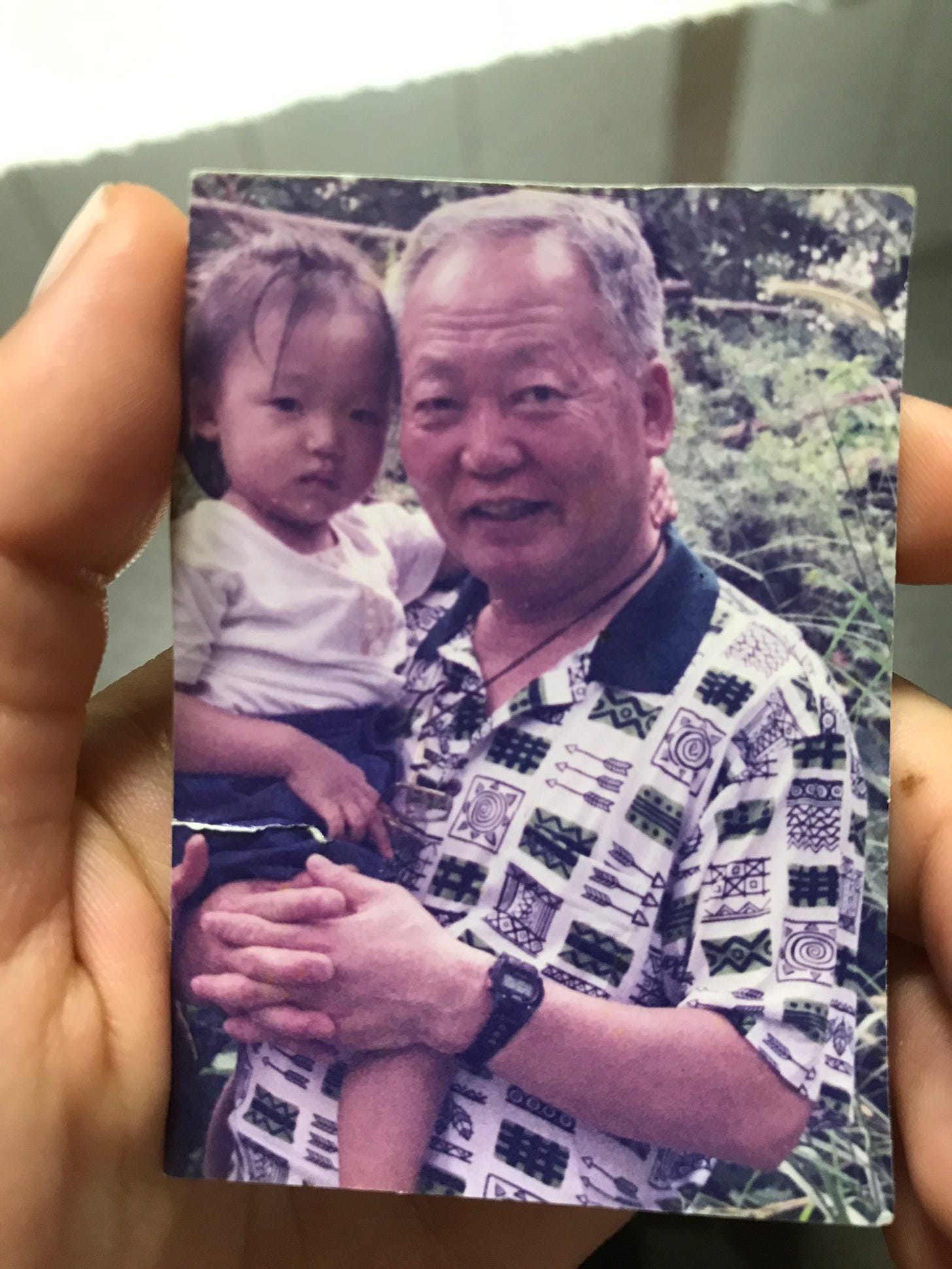

My paternal grandfather passed away in Seoul when I was nineteen, the summer after my freshman year of college. I saw him in early June on my way to Taipei for a summer internship. Then, in late July, I got a call that my grandfather was on his deathbed. My father and I flew to Seoul immediately. Within 24 hours of our arrival, he took his last breath in the middle of the night.

Though he had a large part in raising me, we grew distant after I moved to the States. All I knew about him was that he came from an academic lineage—his father graduated as part of the first medical school class at Seoul National University during Japanese occupation—but he himself didn’t live up to his family’s expectations. He ran an import-export business with the U.S. Army that went bankrupt. My father wept when he passed, from regret.

And though my maternal grandfather is still alive, with him, I’ve experienced a different, gradual loss. After his Alzheimers rapidly claimed him, it’s been years since he’s been the grandfather of my memories. He barely recognizes me or my mother. I haven’t yet properly written or reflected on my grief for the loving, bibliophilic, energetic grandfather I used to know.

I don’t think it’s uncommon for many of us 1.5 or 2nd-generation immigrant kids to feel a distance between ourselves and our grandparents. The distance is both physical and emotional: we might live across the ocean, we might not speak the same languages, and we might not know what questions to even ask them.

When our grandparents pass away, we experience more than just the grief of a single human—we lose all the histories that we never fully recorded. We grieve the fact that with them, dies a root that connected us to our motherland. There’s a severance from our ancestry, which fills me with han—grief and sorrow.

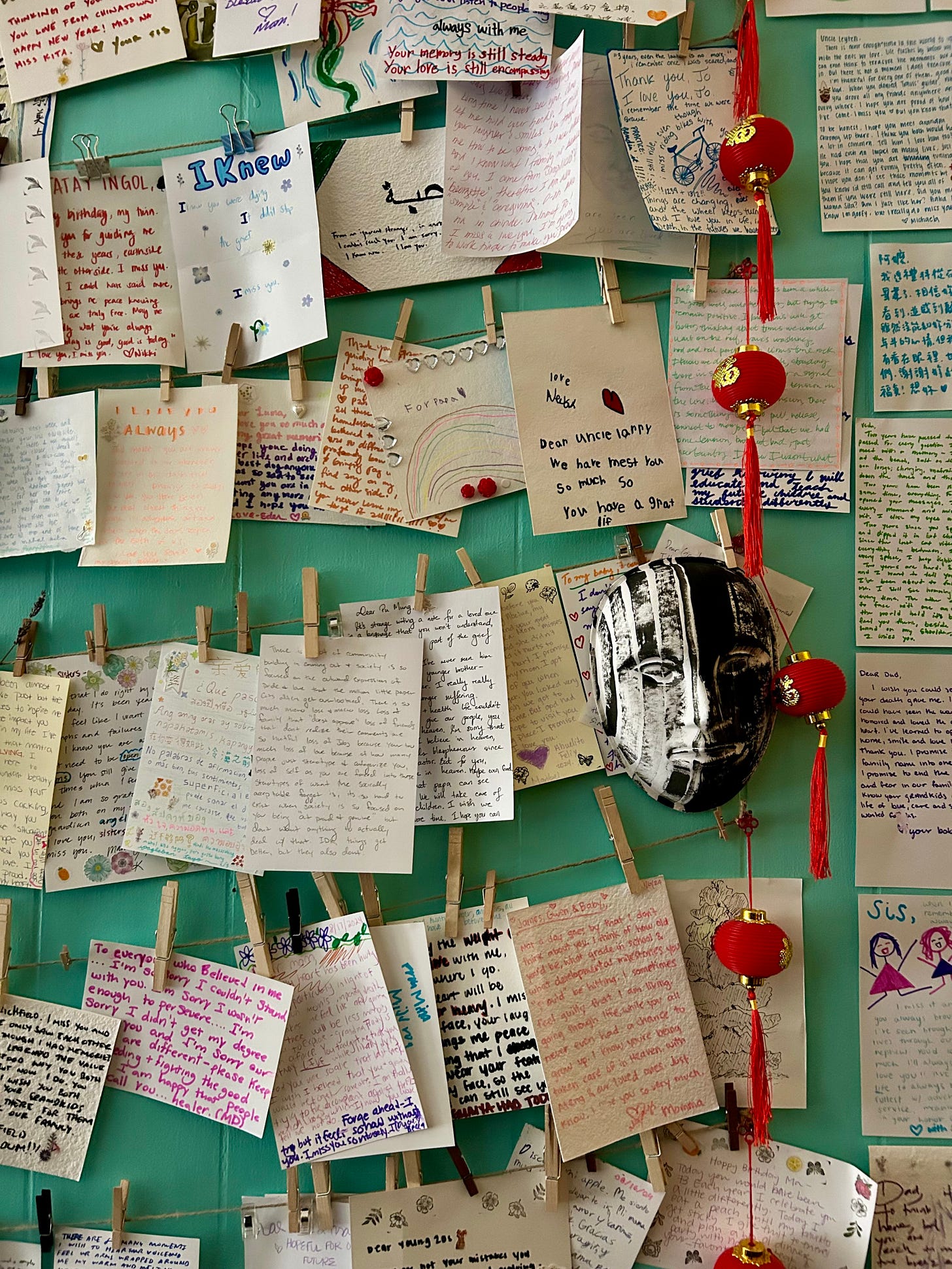

Which brings me to interviewing mourners during Lunar New Year. When I learned about A Resting Place, a grief and loss cultural resource center in Seattle, I jumped at the chance to write a story about its Lunar New Year celebration. The grief space is tucked into a sound bath center in Seattle’s International District. When you walk in, there’s a grief communal altar with pictures of tatays and lolas. There’s a grief letter wall with notes written in dozens of languages. There’s a grief resource library and a grief card deck with prompts that let you reflect on loss. It’s impossible not to feel held by the grief of all the visitors who have ever stepped inside the center.

Derek Dizon, its founder, spoke about grief as a constant state immigrants occupy:

As a person who comes from an immigrant family, I have experienced a lot of grief in my life. Not just the personal death of a family member, but the experiences of displacement, of cultural erasure, of internalized shame. I think that has to do with grief as well. Always grieving a part of your family, a part of yourself, a part of your identity.

Dizon is right—we are always sitting in grief, moving through grief, and yet we don’t always have the language for it. Our lives are moving so rapidly. We forget to ask one another about our grief. I know I’m guilty of not checking in enough on my friends who lost their loved ones. There are moments when I’ve thought about texting them how they’re coping with their loss, but I don’t, because it doesn’t feel like the right time. Or I worry about making them uncomfortable by bringing up their grief.

As an L.A. resident, I’ve been thinking about grief especially as the wildfires die down. It seems like the whole city immediately sprung into action, my reporter self included, as soon as the fires started spreading. It was an incredible and necessary mobilization, to be sure, but I wonder if we gave enough time to people who lost everything in the fires to grieve. I wonder if we gave ourselves enough time to grieve as a city.

Before leaving A Resting Place, I sat down for a half hour and wrote a letter to both my grandfathers in Korean. I’d never acknowledged my grief for them before. Writing it down on the page, then pinning my letter to the wall, seemed like a public and necessary act.

Grief letters I didn’t write:

A letter to my younger self

A letter to the language I’ve lost

A letter to the half of my homeland I may never visit

What would it mean if we could wear our grief visibly? Like a sign hung across our hearts, declaring who or what we are grieving? To my friends who have lost something or someone dear to them, I want to say: I am thinking of your grief always.

Here’s an invitation, inspired by A Resting Place’s communal letter wall: Try writing a letter as you sit with your grief. Share it with someone you love, or if you want, with me.