Every time I return to my birth country, I experience intense body dysmorphia. What sets this apart from a typical body dysmorphia, or a constant obsessive focus on flaws in appearance, is that mine only kicks in when I’m in South Korea.

It’s entirely cultural, caused by a sharp fracturing in my self-perception. In the U.S., my appearance doesn’t cause me active grief, but in Korea, I start to scrutinize every feature on my face and my body. I don’t fit many of the stereotypical beauty or behavioral norms expected of Korean women, and being in the country makes me hyper-aware of myself.

For this Korea trip, I wanted to show up prepared. I signed up for an 8-week Asian Femme Body Journey course with Yellow Chair Collective, an AAPI mental health group, hoping that the course would give me tools to face family members, the language to express my body grief, and a community that I could open up to about my body dysmorphia.

My main goal was to build up my armor for my time in Seoul. Part of my body dysmorphia is physiological; Korean women are on average shorter and weigh less than my 5’6, 135 pound frame. A majority of clothes are only sold in a “one size” that equates to a size small (2-4) in the U.S. But what I’d assumed for most of my life was physiological hides the patriarchy at play—in Korea, where gender inequality is one of the highest among OECD nations, a woman's worth and value increases the less space they occupy. There are rampant rates of eating disorders under a societally-enforced starvation.

Going to Seoul can feel like entering an alternate universe. As I walk around, I battle extreme self-consciousness and anxiety about my body, comparing it to the thinner figures and unblemished faces on the subway or the streets of Seoul. To add to that, family interactions, as harmless as they may seem, bring up a whole host of demons—dissatisfaction with my facial features, my skin, my hips, shoulders, and legs.

The body dysmorphia kicks in intensively and destructively. By around the three-week mark of my trips, I dissolve into a pool of tears from a single casual remark from a family member.

Of course, all of this is relative. I recognize that in the U.S., I’m considered “average” body size, height, and weight, as rooted in all the -isms as those measurements are. I’m aware that in the States, I benefit from certain skinny privilege and beauty standards that have allowed me to gain societal advantages. I know all this about my positionality in the States, which is why it makes it all the more confusing to step into the homeland and feel like such an alien.

The second reason I signed up for the 8-week course to continue unlearning and untangling all the poisonous myths about bodies that I’ve internalized from my Korean and American upbringing: beliefs about whiteness, “beauty,” and thinness that I’ve attached to values about myself and others. I was tired of my own stream of negative self-talk in my head, the resentment and jealousy I felt towards others who met beauty/thinness standards, and the judgments I placed on other people for their appearances. I was excited to unpack all the above with an Asian American femme group.

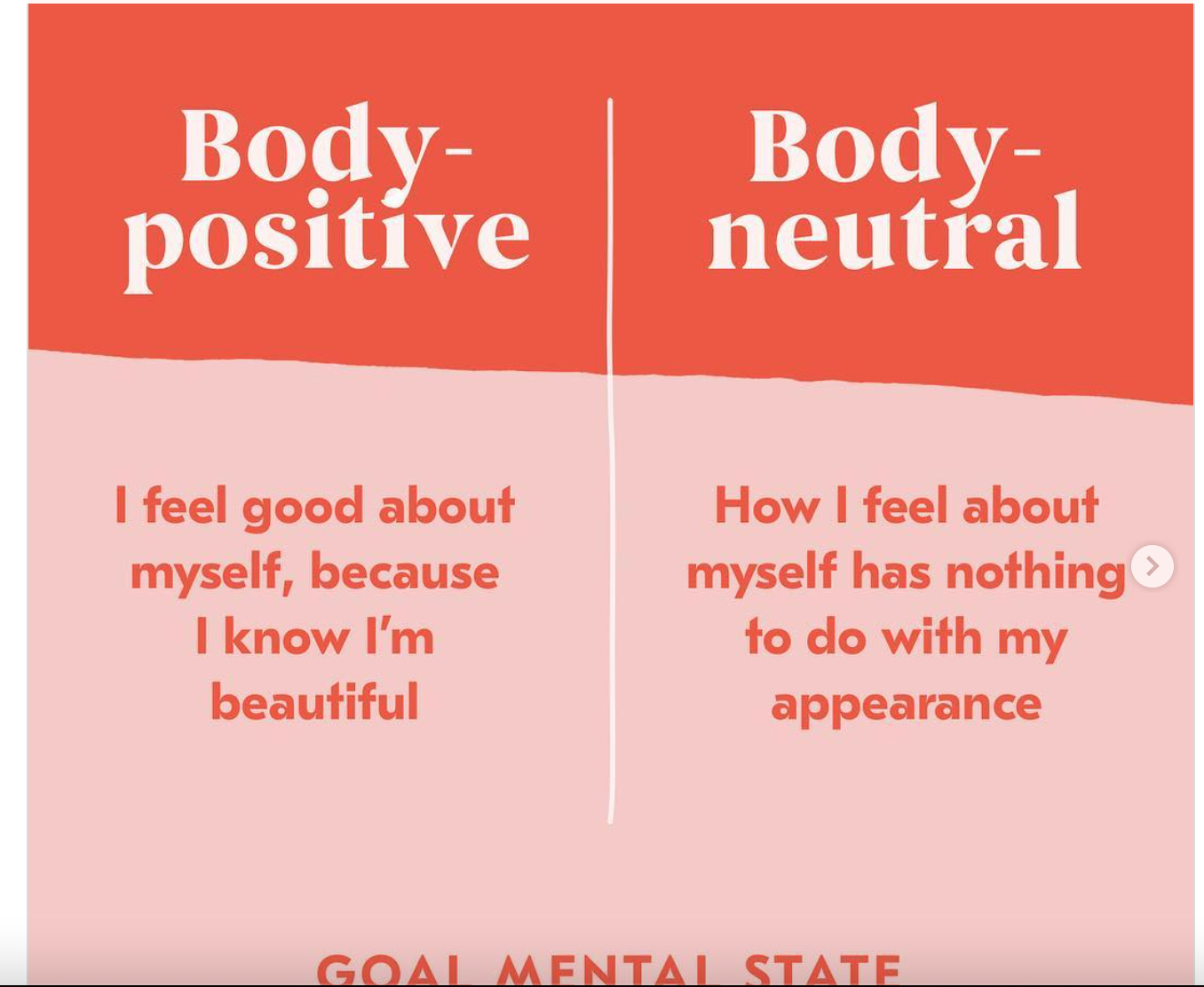

I was interested in this Body Journey group in particular because the curriculum covered body neutrality and body acceptance. Korean feminists have championed these principles over the Western “everyone is beautiful” approach for years (I learned more about the contemporary Korean feminist movement through journalist Hawon Jung’s excellent book Flowers of Fire).

The Western, body-inclusivity version of “everyone is beautiful” has long been co-opted by the capitalistic order, masquerading an expansion of beauty standards (like Dove’s campaigns) only to quickly reverse trend as TikTok re-codified White, Eurocentric, age-ist beauty standards. There is simply too much profit to be made through Kbeauty and weight-loss drugs that promise whitening, face-slimming, and anti-aging.

In the midst of all this beauty regression, I’ve been inspired by Korean feminists’ emphasis on body neutrality. They recognize that Korean society is so hypercapitalistic and heteropatriarchal that to feel “beautiful” about oneself is simply impossible both financially and physically. Instead, these feminists have tried to de-value appearance entirely instead, asking: what if we acknowledged that physical beauty is a patriarchal construct and aspired towards a world where we are valued for qualities outside of our appearance? Body neutrality is about shifting the value we place on one another human beings from physical appearance to other, non-physical traits.

From the start, our group had a range of Asian American participants of varying ages. We compared and contrasted beauty standards across Japanese, Filpinx, Korean, Vietnamese, and Chinese cultures, nodding along whenever someone made a comment that resounded painfully.

In Week 1, we tracked for three days whenever our negative inner voice would speak to us about our bodies. We were to write: the trigger that made the voice speak up (ex. seeing yourself in a photo, or scrolling through Instagram.), the exact phrase the negative voice used (ex. “you look enormous right now”), and our response (ex. feeling shame, sadness, cutting out carbs). For 72 hours, I dutifully tracked each time the voice surfaced.

I ended up writing down more than a dozen instances of negative self-talk. I knew I didn’t necessarily think kind thoughts about my appearance all the time, but I came away from the exercise shocked to actually see, on the page, how many times I berated myself for my appearance throughout the day. I teared up at how vitriolic my inner voice sounded, asking, how could I be so cruel to myself, and what sort of toll did this take on my psyche?

In Week Two, we brainstormed responses to toxic comments about our bodies. I mentioned a few TikToks like “10 Things To Say To Your Family Members About Your Body During the Holidays” that I’d seen shared on social media. All of these advised viewers to respond strongly to body comments with defenses like, “I am NOT accepting comments about my body at this time,” or “Talking about my body is off-limits.”

I told the class how I’d never found these videos helpful because of their strict boundary-drawing. The cultural relationship that I had with the elders of my family, who frequently commented on my body, was that of respect and blurred boundaries. If I wanted to keep operating within my family system, I needed to navigate conversations at opportune moments with carefully balanced words.

“What if I chose to be vulnerable instead?” I asked. “If a body comment comes up while I’m alone with a relative, I can tell them that I’ve struggled with my body image in the past when I’m in Korea and that I’m on a journey towards compassion and body acceptance.” My classmates agreed that this might get through to my relatives in a way that wouldn’t make them defensive.

In Week 4, we covered “body grief.” Our group was intergenerational, and the members resonated with the term in different ways. I learned that “body grief” meant grieving the bodies we used to have, the ideal body we’d craved, or any changes in appearance, mobility, or strength. The facilitators encouraged us to write a goodbye letter to one of those. I chose to write one to the ideal Korean body, the one I’d wished for my whole life. Dear ideal body, I wrote. This is one of probably many break-up letters. You take away precious time and mind-space to be grateful and be present in the body I have now. Good riddance, and goodbye.

In Week 5, we were encouraged to write a love letter to the parts of our bodies we hated. That one threw me for a loop. A love letter? To my body, which I’d only ever felt dissatisfied by? Dear sacred body, I wrote. Thank you for holding me through beauty, pain, and grief. Then to the parts of myself I was insecure about: thank you, hips, for cradling me during long hikes. Thank you, squishy tummy, for holding all the food I love to eat. Thank you, wide shoulders, for helping me take up more space in the room.

All these writing exercises helped me think of my body as a separate, precious entity that I could enter into direct conversation with. Separating myself from my body forced me to view my body as a precious Other, and not a part of the Self that I could so easily disparage. The letter allowed me to write as if to a loved one, and simply express gratitude for all the times that my body had taken care of me, even when I had starved and numbed it.

And so, armed with all the tools from the Body Journey group, I set off for my monthlong homeland trip, preparing myself for the worst, but holding onto hope for the productive conversations that might come out of my vulnerability.

But I quickly came to realize that the body challenges I dealt with in Korea weren’t the ones I’d spent so many weeks preparing for.

…to be continued!